This fall, the doors to the vestibule connecting Woolsey Hall with the newly christened Schwarzman Center will open after years of renovations, and students will once again stream through this central passageway of campus. That pathway will lead them to the modern additions to the building, redesigned to serve as a hub for student activity, but it also bears fading letters of poetry that prove a portal to an earlier transformation of the space of national significance: Yale’s Civil War Memorial

Before the Schwarzman renovations began, the stanza, engraved into the floor as the conclusion of the inscription to the memorial, was often covered by mats.1 But when the memorial was dedicated in 1915, the now-obscure and faintly legible lines, written by Francis Miles Finch, Yale College class of 1849, were well known:

No more shall the war-cry sever,

Or the winding rivers be red;

They banish our anger forever

When they laurel the graves of our dead!

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment day; —

Love and tears for the Blue,

Tears and love for the Gray.

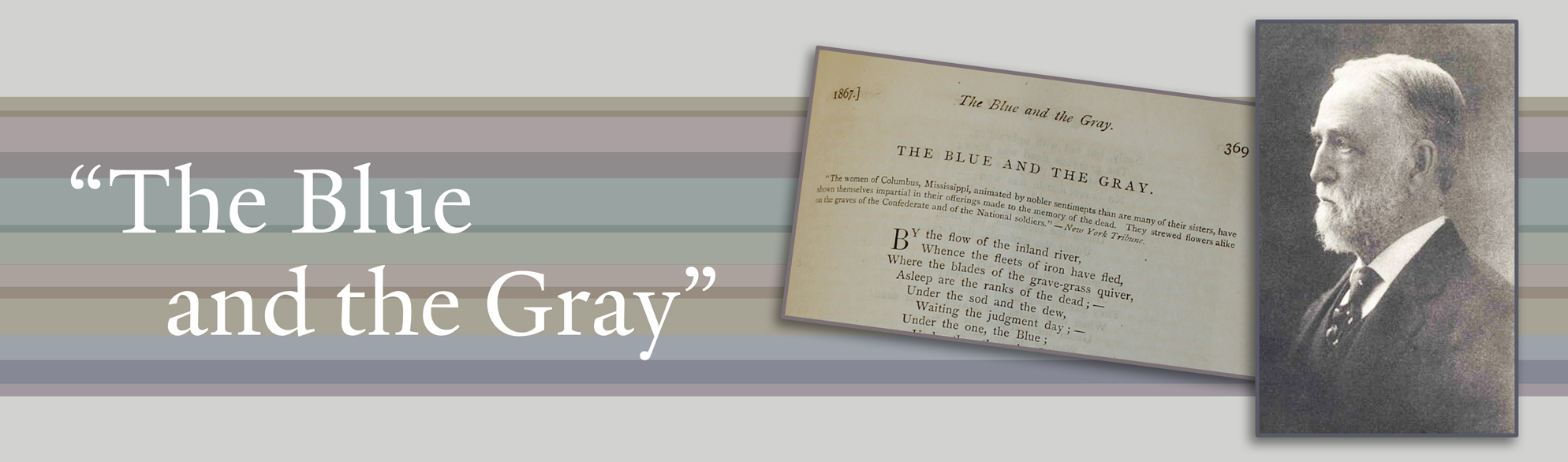

The inscription quoted the final stanza of Finch’s poem “The Blue and the Gray,” which he published in The Atlantic Monthly in September 1867.2 Newspaper editors widely reprinted the poem, from Bridgeton, New Jersey to Helena, Montana and from Portland, Maine to Alexandria, Louisiana.3 For decades, it frequently appeared in papers’ Memorial Day editions, as the grieving nation paid respects to the 750,000 Americans it buried in the Civil War.

The designers of Yale’s memorial, of course, selected Finch’s words for the inscription not merely for their ubiquity. Rather, the poem embodies the spirit of sectional healing and reconciliation that defined the design of and philosophy behind Yale’s Civil War Memorial. Of equal concern to the researchers of the Yale and Slavery Working Group is what the inscription does not say, and the history it declines to commemorate. Finch’s faded poem, etched into the foundation of Yale’s campus, offers a key to recovering the little-known history of how Yale remembered the Civil War, 50 years after it ended—and what it forgot.

A poet and lawyer, Francis Finch became an appeals court judge in New York and a trustee of Cornell University.4 He is said to have drawn his inspiration for “The Blue and the Gray” from a brief item that made its way into the New-York Tribune in 1867. In Columbus, Mississippi, the Tribune relayed, women “animated by nobler sentiments than many of their sisters” decorated the graves not only of the Confederate dead but those of Union soldiers, too.5 Finch’s third stanza appears to recreate this episode:

From the silence of sorrowful hours

The desolate mourners go,

Lovingly laden with flowers

Alike for the friend and the foe; —

Under the sod and the dew,

Waiting the judgment day; —

Under the roses, the Blue;

Under the lilies, the Gray.

Transforming this anecdote into poetry, Finch eternalized a powerful symbol of reunion. The war was over, and both “the friend and the foe” had reason to grieve. According to Ellsworth Eliot, who wrote Yale in the Civil War in 1932—and for whom Finch’s sentimental tone continued to resonate—“The Blue and the Gray” was “a vital factor in dissipating the feelings of bitterness and hostility engendered by the war and in replacing them with the spirit of charity and reconciliation so essential to the restoration of an undivided union.”6 The poem, then, captured perfectly the aspirations of Yale’s designers of the Civil War Memorial. The memorial tablets included the names of all Yale alumni who died in the War, Union and Confederate. In the words of one organizer of the effort, the memorial was “designed to do justice at last to the high devotion to principle and the courage of those who fought on both sides in the Civil War.”7

Not every alumnus shed tears equally for the Blue and the Gray. One graduate, upon receiving a solicitation to contribute to the memorial, wrote to a member of the committee expressing a starkly different interpretation of the war—or, as he termed it, “the slaveholders’ rebellion.” “I do not believe in the ‘high devotion’ of men who fought four years to strengthen and perpetuate human slavery,” he wrote. “I do not believe that the leaders of this infamous conspiracy against human rights and life ‘thought they were right’ as their apologists now claim they did and I do not think that all distinctions between right and wrong, treason and loyalty, should be ignored […].”8 The writer refused to accept the memorial’s neutrality about the causes for which each side fought.

Yet this objection was the exception to the rule, and it marks one of the few instances in which the word “slavery” appears in Yale’s archives on the memorial. Anson Phelps Stokes Jr., the secretary of Yale, reported in 1913 that less than half a dozen alumni had written to the university criticizing the memorial, whereas “hundreds, including many identified with the Union cause, have indicated their appreciation” of a memorial that symbolized “that the wounds of the nation have been healed.” Responding to a rare piece of criticism, Stokes reached for Finch’s words: “The spirit which has actuated the committee is given in […] ‘The Blue and the Gray.’”9

In the years after the dedication of the Civil War Memorial, Yale students passing through Memorial Hall adopted the custom of removing their hats to pay respects to the 168names carved into the tablets.10 Over time, students’ awareness of and reverence for the history beneath their feet has dimmed. Peeling away the rugs, they will find the long-forgotten words of Francis Finch. And if they stop, for a moment, as their predecessors once did, they will also hear silences, the voices of those left out of Finch’s poetry, silences on which the Civil War Memorial, and the story of Yale itself, were built.

— Steven Rome, Yale College 2020

Notes

1 For this detail and a recent narrative of Yale’s Civil War Memorial, see Ali Frick, “‘The Mingled Dust of Both Armies,’” Yale Alumni Magazine, Sept./Oct. 2011, https://yalealumnimagazine.com/articles/3279-the-mingled-dust-of-both-armies?page=1. Frick, who graduated from Yale College in 2007 and Yale Law School in 2012, wrote her Senior Essay in History on the memorial.

2 F. M. Finch, “The Blue and the Gray,” The Atlantic Monthly, Sept. 1867, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1867/09/blue-and-gray/590320/.

3 Newspaper records accessed via the Library of Congress’s Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers database, at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/. See Helena Herald, July 1, 1875; West-Jersey Pioneer, May 29, 1874; Portland Daily Press, June 1, 1872; The Louisiana Democrat, July 14, 1869.

4 Leo Weldon Wertheimer, ed., The Twelfth General Catalogue of the Psi Upsilon Fraternity (Executive Council of the Psi Upsilon Fraternity: 1917), 74.

5 Quoted and reprinted in The Bedford Gazette, Oct. 11, 1867, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82005159/1867-10-11/ed-1/seq-1/?date1=1867&index=12&date2=1916&searchType=advanced&language=&lccn=&proxdistance=5&state=&rows=20&ortext=&proxtext=&phrasetext=%22love+and+tears+for+the+Blue%22&andtext=&dateFilterType=yearRange#words=%5Bu%27Blue%27%2C+u%27love%27%2C+u%27Love%27%2C+u%27tears%27%2C+u%27Tears%27%5D; see also Ellsworth Eliot Jr., Yale in the Civil War (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1932), 70; and New-York Tribune, May 29, 1904, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1904-05-29/ed-1/seq-29/.

6 Eliot, Yale in the Civil War, 70.

7 Talcott H. Russell, “Report of the Committee on Memorial to Yale Men Who Lost their Lives in the War between the States,” June 18, 1912.

8 D. E. Burton to Frank Polk, [n.d.], 1915. Secretary’s Papers, Yale University, Records (RU 49), Series II, Box 22, Folder 287. Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library. https://archives.yale.edu/repositories/12/resources/2873.

9 The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, Dec. 5, 1913, accessed via Library of Congress, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022472/1913-12-05/ed-1/seq-7/.

10 Yale Daily News, May 8, 1925, https://ydnhistorical.library.yale.edu/?a=d&d=YDN19250508-01.2.6&e=02-10-1915-02-10-1915–en-20–1-byDA-txt-txIN——-.