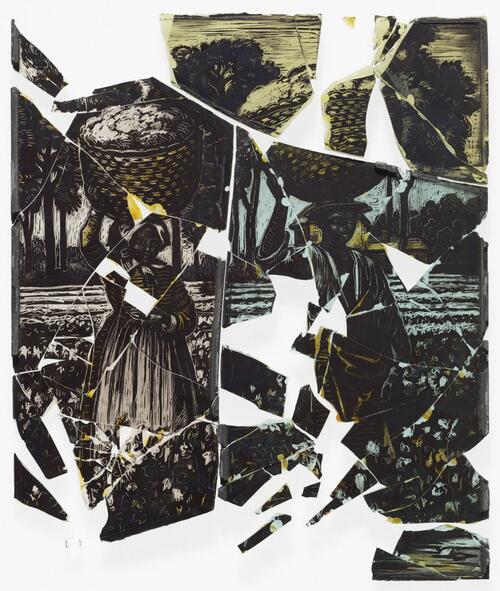

On a summer day in 2016, a worker in the dining hall at Calhoun College, a residential building on the campus of Yale University, broke a window. “I took a broomstick,” he later recounted, “and it was kind of high, and I climbed up and reached up and broke it” (1). He hit the pane twice before the various pieces dislodged from their frame, fell to the ground, and shattered. It was an act of protest that the worker, Corey Menafee, felt was justified by the window’s subject matter. Painted in grisaille highlighted with touches of amber, two enslaved figures stood in a field of cotton, each with a large basket of cotton balanced on their heads.

D’Ascenzo Studios, Cotton Field (broken), Philadelphia, 1932. Vitreous enamel on plate glass, 12 × 91⁄4 in. (30.5 × 23.5 cm). Yale University

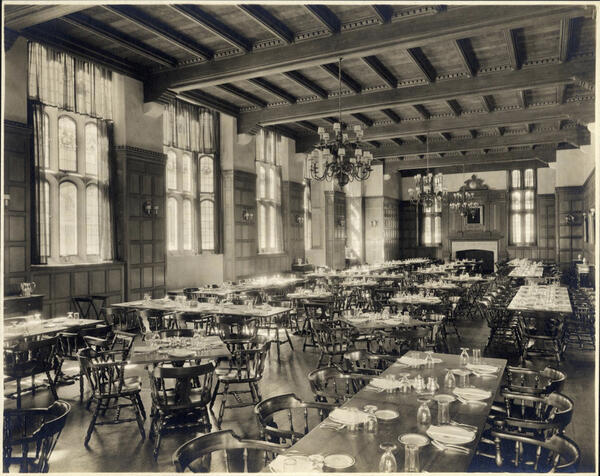

It was one panel in a larger composition commemorating the American South that expands across the main windows of the Calhoun College dining hall. Some panes illustrate native plants, while indigenous animals crawl across others. Only a handful show the presence of humankind, but those that do project an antiquated view of the South. They are as sepia toned in their subject matter as they are in their coloration.

The windows were created by D’Ascenzo Studios, a stained-glass workshop founded in Philadelphia in 1898 by the Italian immigrant Nicola D’Ascenzo. The studio received the commission for Calhoun College through the building’s architect, John Russell Pope. The windows in this new building deliberately looked old, mirroring the Gothic-inspired architecture, yet they were based on modern source materials that ranged from book illustrations to popular prints. It was decided that the windows in the common room of Calhoun College, one of the seven residential buildings that opened in 1933, would feature the eponym of the college—John C. Calhoun—while the windows in the dining hall would present scenes of the South.

The windows were products of their time and place, created in 1932 by a firm in Philadelphia for a client in New Haven. The few panes that included people depicted a view of the South that pastoralized sustained racism under a gauze of nostalgia, in keeping with Lost Cause narratives about the Civil War. These narratives elided the devastating realities of the South’s slave-based economy and recast the Civil War as “an honorable sectional duel, a time of martial glory on both sides, and triumphant nationalism” (2).

Calhoun College Dining Hall, New Haven, ca. 1932–59. Photographs documenting residential colleges at Yale University (RU 632). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

The breaking of the dining hall window coincided with larger conversations on Yale’s campus about the experiences of minority students and the legacy of John C. Calhoun. In 2017 Calhoun’s name was removed from the college, and the building was renamed after the pioneering computer scientist Grace Murray Hopper. These conversations, in turn, echoed national debates embodied by the Occupy and Black Lives Matter movements over race, police violence, and social inequality, and public battles over the iconography and placement of Civil War monuments. The interpretation of art evolves. Art can reflect its ever-evolving cultural sur-roundings, especially when installed in public settings. Art has the power to move people. This episode serves as a reminder that art is and continues to be a vital part of our society. Images have power, and while a window may be just a piece of glass to some, it can encompass whole worlds to others.

A committee co-chaired by Julia Adams, Head of Hopper College, and Anoka Faruqeee, professor in the School of Art, have commissioned new windows for the common room and dining hall from artists Barbara Earl Thomas and Faith Ringgold. These windows are planned to be unveiled in 2022.

John Stuart Gordon

Benjamin Attmore Hewitt Associate Curator of American Decorative Arts, History of Art, Yale University

Adapted from: John Stuart Gordon, American Glass at Yale (New Haven: Yale University Art Gallery in association with Yale University Pres, 2018)

Notes:

1. Corey Menafee, in Daniela Brighenti, Qi Xu, and David Yaffe-Bellany, “Worker Smashes ‘Racist’ Panel, Loses Job,” New Haven Independent, July 11, 2016. 2. Alan T. Nolan, “The Anatomy of the Myth,” in The Myth of the Lost Cause and Civil War History, ed. Gary W. Gallagher and Alan T. Nolan (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 12.

Captions:

1. D’Ascenzo Studios, Cotton Field (broken), Philadelphia, 1932. Vitreous enamel on plate glass, 12 × 91⁄4 in. (30.5 × 23.5 cm). Yale University

2. Calhoun College Dining Hall, New Haven, ca. 1932–59. Photographs documenting residential colleges at Yale University (RU 632). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library