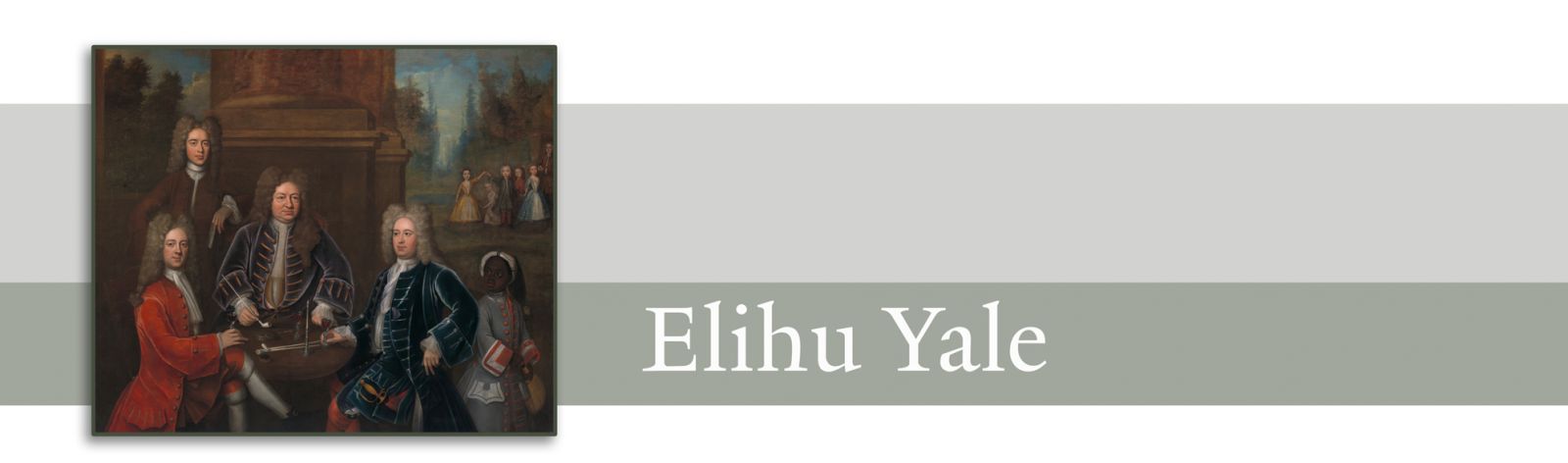

Attributed to John Verelst, Elihu Yale with Members of his Family and an Enslaved Child, ca. 1719. Oil on canvas. Yale Centre for British Art, Gift of Andrew Cavendish, eleventh Duke of Devonshire.

This rendering of the oil canvas of Elihu Yale (1649–1721) displays his wealth, grandeur, and prestige near the end of his life. The accompanying unnamed and collared enslaved child, like Yale, represented the expansive network of the British empire, though they characterized two very distinct poles of early modern globalization. Yale was born in New England in 1649 to a family who moved to Britain when he was a child. He spent his administrative career in India, and returned to England and Wales to see out his days as a wealthy retiree. A significant change that occurred over the course of Yale’s life was Britain’s emergence as a dominant force in the Atlantic, and with that, the establishment of a Triangular Trade. By the eighteenth century, Britain’s economy was inexorably bound to chattel slavery, and London awash with its profits. Elihu Yale was product of a rapidly changing and increasingly connected world. In contrast, the unnamed and collared enslaved child represented the growing population of enslaved people, whose commodified bodies and labor financed some men’s status and wealth.

Simultaneously, the East India Company (EIC) continued to grow its influence on the subcontinent of India, and from its factories along the coastlines, oversaw company shipping that–amongst other cargo–carried enslaved people across the Indian Ocean in a slave trade of smaller volume than that of the Atlantic world. In 1688, as Governor and President of Fort St. George, the East India Company factory at Chennai (then known as Madras) Elihu Yale and his council acquiesced to pressure from their Mughal hosts and neighbors to prohibit the purchase or shipping of slaves from Chennai or nearby port upon pain of fines, but it is not clear as to what extent this policy was ever enforced. Nor is it clear to what extent Elihu Yale profited directly from involvement in either the Indian or Atlantic slave trades. And, efforts to uncover this information have been frustrated by the loss of his person papers. Like many EIC operatives Yale certainly enriched himself through private ventures– namely, the extractive and exploitative trade in precious stones, which generated vast wealth off the backs of cheap labor. After being deposed from EIC leadership in 1692, Yale eventually returned to England, where he posed for this portrait. He also responded to donation requests from the Collegiate School of Connecticut, which, in gratitude for gifts that had made him its greatest benefactor, changed its name to Yale College.

In England, Yale displayed his wealth in the objects he acquired from places across the British empire, objects such as artwork, fine cloth, and the ruby ring he wore in this portrait. Eighteenth century portraits of wealthy Britons, like Yale, frequently featured depictions of enslaved children dressed in fashionable attire and often included a collar. These children were purchased and enslaved from the expanding West African and East Indian slave trades. In the portraits, they served as markers of the social status of the main subjects. While it remains unclear if Yale owned this enslaved child, Yale’s status and wealth were nonetheless reinforced by his presence. Additionally, there is no doubt that Elihu Yale was comfortable having his portrait made alongside figures who were demonstrably enslaved. His relatives in New Haven were slave holders; the company he worked for oversaw slave-shipping in the Indian Ocean; and even in London, where the law did not make provision for existence of chattel slaves, Yale and his sons-in-laws chose to have their portrait made alongside an enslaved child over whom they would have claimed ownership.

Yale University - now one of the oldest and wealthiest institutions in the United States - has commissioned its own investigation of Elihu Yale and his ties to slavery as part of a larger initiative to uncover the relationship between Yale University and slavery.

—Teanu Reid, PhD candidate in African American Studies and History at Yale University, and Edward Town, Head of Collections Information and Access at the Yale Center for British Art

For more information about the portrait featured on this page, visit the Yale Centre for British Art’s online essay, “New light on the group portrait of Elihu Yale, his family, and an enslaved child”: https://britishart.yale.edu/new-light-group-portrait-elihu-yale-his-family-and-enslaved-child

and: “at home: Art in Context | New light on a portrait of Elihu Yale, his family, and an enslaved child,” A talk by Edward Town, Head of Collections Information and Access at the Center, discussing this work in the Yale Centre for British Art’s collection: https://britishart.yale.edu/exhibitions-programs/home-art-context-new-li…

Bibliography

Primary Sources

1. Yale University - Elihu Yale Papers (Manuscripts & Archives at Sterling Memorial Library), Box 1 at MSSA, Folder 7 – Diary and Consultation Book, 1687

2. Yale University - Treasurer’s Records, Benefactors, General Histories, Group YRG5-B, Series IV, Box 370

Secondary Sources

3. Austen, Ralph A. “Monsters of Protocolonial Economic Enterprise: East India Companies and Slavery Plantations.” Critical Historical Studies 4 (Fall 2017): 139–177.

4. Kuebler-Wolf, Elizabeth. “‘Born in America, in Europe Bred, in Africa Travell’d and in Asia Wed’: Elihu Yale, Material Culture, and Actor Networks from the Seventeenth Century to the Twenty-first.” Journal of Global History 11, no. 3 (2016): 320-43.

5. Sudan, Rajani. “Connecting lives: Elihu Yale and the British East India Company.” In Transnational Lives: Biographies of Global Modernity, 1700–Present, edited by Desley Deacon, Penny Russell, and Angela Woollacott, 133-143. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

6. Yale Center for British Art. “Elihu Yale, the second Duke of Devonshire, Lord James Cavendish, Mr. Tunstal, and a Page.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://interactive.britishart.yale.edu/slavery-and-portraiture/266/elih…

7. Yale Center for British Art. “New Light on the Group Portrait of Elihu Yale, His Family, and an Enslaved Child.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://britishart.yale.edu/new-light-group-portrait-elihu-yale-his-fami…

8. Yale Center for British Art. “Timeline 1649-1722.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://britishart.yale.edu/stories/new-light-group-portrait-elihu-yale-…

9. Yale Center for British Art. “Timeline 1734-1964.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://britishart.yale.edu/stories/new-light-group-portrait-elihu-yale-…

10. Yale Center for British Art. “Timeline 1969-2021.” Accessed June 1, 2021. https://britishart.yale.edu/stories/new-light-group-portrait-elihu-yale-…

11. Yannielli, Joseph. “Elihu Yale was a Slave Trader.” Last modified November 1, 2014. http://digitalhistories.yctl.org/2014/11/01/elihu-yale-was-a-slave-trader/